In his book Understanding Media: The Extension of Man (1964), Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase “The medium is the message”. He argued that it was the medium itself that shaped and controlled “the scale and form of human association and action”. Neil Postman in Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985) went one step further and stated, “The medium is the Metaphor,” arguing that each medium is appropriate for a different kind of knowledge. Written text, for example, is ideal for something like law-making. Once written down, it leaves little room for interpretation. Visual mediums like images or movies leave more room for interpretation, which leads us to Judith Leyster’s painting.

A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel was painted in 1635, almost four centuries ago. At first sight, most of what we see is still recognizable; the kids (but they do look somewhat old), the cat (which looks like “our” cats, if you feed this image to a machine learning vision model for cat recognition, it will classify it correctly), but probably not the glass-eel which by now is rare. If you leave it at that, it is just a nice painting of some children, be it somewhat old-fashioned (no wonder after 400 years).

But if you look slightly closer at the details, you notice a couple of things. The girl looks straight at us. Her right index finger is raised, and with her left hand, she’s holding the cat’s tail. Her facial expression indicates she’s aware of something.

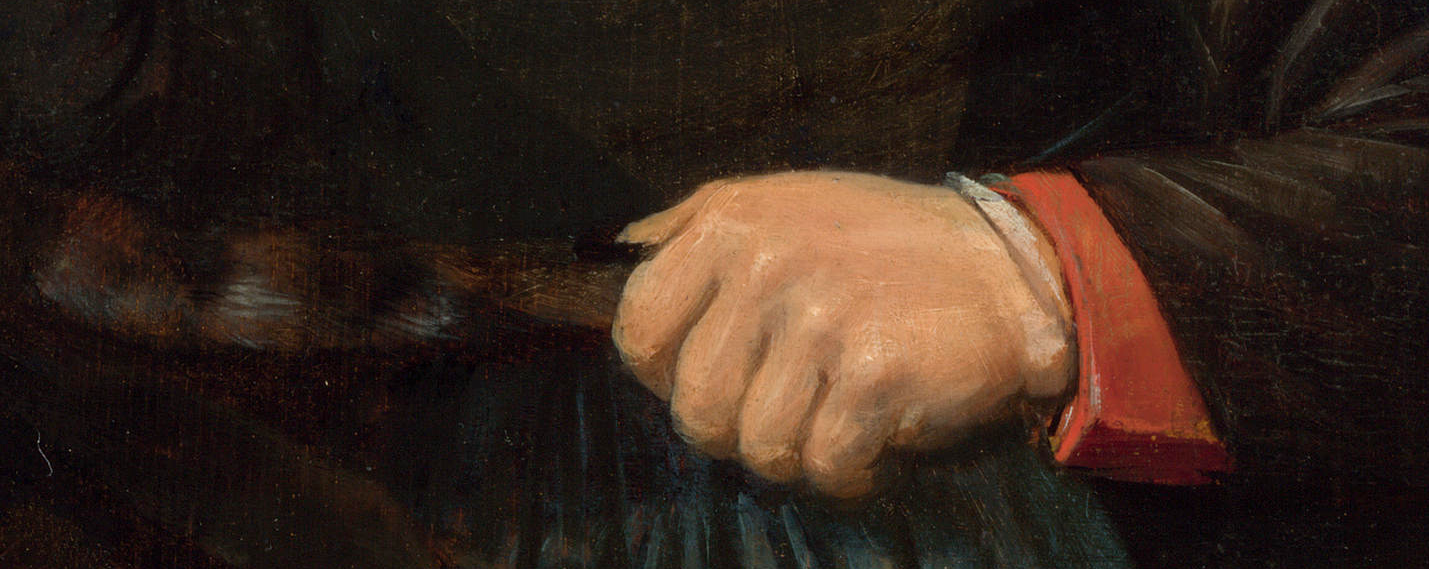

The boy has his head tilted backward, his eyes as far right as he can get them. He’s clearly not looking at us, and at the same time, we have no idea where he’s looking at, maybe at an adult outside our line of sight. In his right arm, he’s holding a cat. Like the girl, it is looking straight at us, and although it has its paws spread out, it doesn’t appear to be struggling. His left arm is raised, and in his hand, he’s holding a glass-eel. The way he looks seems like a mix of happy expectations and awaiting approval for something he’s about to do.

Added up, it feels like the composition of the painting means more than just a depiction of two children. But how do you make sense of something that is literary from another time? And even more interesting, would the meaning of the painting have been obvious to someone from the 17th century?

Let’s give it a try. The first clue is the finger the girl is holding up. This gesture is something that was often used in paintings from that period to indicate a moral lesson is to be learned. The meaning of the gesture hasn’t changed much, as a raised finger still signals a warning of some kind(at least in Western culture). But what is the moral lesson given this context of a girl, a boy, a cat, and an eel?

Over time a number of explanations have been given (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Boy_and_a_Girl_with_a_Cat_and_an_Eel ), but many of them are not very satisfying given what we see. That the boy is teasing the cat by withholding the eel is unlikely; as we noticed before, the cat is looking at us and doesn’t pay any attention to the eel. Also, the allusion to katte-kwaad (Dutch for mischief) is not very strong. The cat is still unharmed and doesn’t look uncomfortable.

One explanation I haven’t seen yet, is the following. The glass eel the boy is holding in his hand is a snake-like, slimy fish that is ideally suited for frighting the girl. He is holding it behind the girl’s head, out of her sight, and he can show it to her by surprise. In this scenario, the boy is looking up to the unseen adult, half laughing about what he is going to do with the eel and the fright it will give the girl when he suddenly holds it before her eyes. But the girl is prepared, she’s already holding the cat’s tail, and when she pulls it hard, the cat will certainly scratch the boy. The moral lesson being that when you bully someone, you can expect revenge (so don’t do it).

But a painting offers us only a frozen moment in time, and as such, it has the potential for a future in which a lot (including the explanations above) might happen. On the one hand, explanations like these make sense, but they also feel kind of simplistic. Keep in mind that oil paintings were not mass-produced like today’s prints and also not meant for children. A simple moral message isn’t worth all the time and effort to make a painting of it.

In addition, this composition also seems too subtle to get the moral message across. If you skip a few timeframes into the future showing the moment where the boy frightens the girl with the eel and where she had already pulled the cat’s tail, causing it to scratch the boy, the message would be much clearer.

This brings us back to Neil Postman’s remarks about the medium. The only information a static image like a painting can contain is limited to a small moment in time. Information about everything that happened before, or will happen after, is hidden from us. The only thing we as viewers can do is make educated guesses. As a painter, you are aware of these limitations, and master painters will pick a composition that best conveys their intentions. But let’s return to the question of if this mischief moral lesson was worth a painting.

If you look at some of today’s (animated) children’s movies, they, of course, tell a relatable and amusing tale for children. But in addition, their makers add a layer of jokes and references that will only be picked up by an adult public. This makes them enjoyable for both children and their parents. It might be that Judith Leyster used the same trick in this painting. On one level, it shows the basic moral lesson of mischief that won’t go unpunished. But what additional (adult) level can we distinguish? To answer this question, we need to use a metaphorical perspective.

In her master thesis, DE KAT EN HET GENRESTUK (The cat and the genre piece), Justa Vuister examines the hidden meaning of cats in 17th-century paintings. One possible meaning is erotic, and she argues that cats are often used in paintings where the moral lesson is something related to sexuality you should not do (like adultery). But what about the glass-eel? In erotic rhymes from the 17th-century, the eel was associated with the male sex organ. Catching the eel had a very specific sexual connotation. On this layer, Leyster’s painting would have a sexual moral lesson; the boy is holding both the cat and the eel, making it easy to bring them together (and given his expression, looking forward to it). While the girl holds on to the cat, a warning finger in the air showing us this should not be allowed to happen. It could well be that Leyster used both layers; the obvious but innocent mischief by kids and the more hidden and less innocent sexual mischief by a girl and a boy, combined in one painting. And you can imagine you can safely put it on public display where the adults enjoy the obvious (for them) sexual connotation of the painting, while the children appreciate just the mischief with the cat and the eel.